Ten (+1) not so well-known facts from IKI history

+1

Space Research Institute (acronym IKI) was established as the leading institute for outer space exploration for the benefit of fundamental sciences within the USSR Academy of Sciences. IKI was founded under the Decree of the Council of Ministers of the USSR of May 15, 1965 No. 392-147 and in accordance with two Resolutions of the Presidium of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR: 1965 No. 403-006 of July 9 and No. 588-014 of August 5, 1966. The former document is archived (AP RF. F.93. Collection of resolutions and orders of the Council of Ministers of the USSR for 1965. Certified copy on letterhead) and published in the book “The Soviet Space Initiative in State Documents. 1946–1964”, ed. by Yu. M. Baturin (Moscow: RTSoft Publishing House, 2008).

1

Space Research Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences was established in 1965, but until 1967 it was named the “Institute (or Organization) PO Box 2286” in the documents.

2

IKI’s main stretched (about 400 m in length) building along Profsoyuznaya Street was built only by 1973. At first, its employees occupied various places: in the Institute for Applied Mathematics at Miusskaya Square, in semi-basement rooms of dwelling houses on Nizhnyaya Maslovka and others. The first IKI’s buildings in Profsoyuznaya Street — employees call them “glasses” — were built in the late 1960s. They exploit the project of a typical hairdresser of that time. Only a few years later, the staff moved to a new building, which has become the hallmark of IKI.

“Glasses” also remain in the inner territory of the Institute. One of them is them now hosts the Chair for Space Physics of Moscow Institute for Physics and Technology.

3

Even though the esthetical value of IKI’s building is arguable, it is worth knowing its architect — Yuri Pavlovich Platonov. Moscow people know him for the complex of buildings — new Presidium of the Russian Academy of Sciences near Gagarin Square and for Europe Square ensemble near Kievsky railway station. By the way, not only IKI occupies the building in Profsoyuznaya Str. Together with it, Institute for Earthquake Prediction Theory and Mathematical Geophysics, the Center for Forest Ecology and Productivity, and part of Keldysh Institute of Applied Mathematics are located there. All of them are also organizations of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

4

When IKI was just founded, it included the staff and laboratories of more than 20 organizations of the Academy of Sciences, universities, industrial enterprises, and various governmental organizations. According to M.V. Keldysh, who had conceived the idea of IKI, the future institute was supposed to “unite” those specialists who had been already working in space science. To emphasize the idea, Keldysh used the word ‘Joint’ in the notes concerning the institute (you may find similar model in the name of the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna, Russia). For various reasons, the idea was not fully implemented, and several “space teams” did not move to IKI. Had it been according to Keldysh's plan, the acronym would have sounded OIKI.

5

Although it is difficult to name the “first” project of IKI, it may well be Cosmos-261. A tragicomic story goes with it. On one (very unhappy) day, the basement of the ordinary house in Nizhnyaya Maslovka street was flooded. Water damaged scientific instruments, which were prepared for Сosmos-261 spacecraft by the staff of the IKI’s laboratory led by Yuri Galperin (see fact No 2). Despite this, the people managed to build them anew, and the satellite was successfully launched on December 19, 1968.

The core of the scientific program in IKI’s first years were missions to Mars and Venus, to be launched in the 1970s. The first large project, Mars-69, unfortunately, was not implemented because of the launchers’ failures. The first successes came with missions Mars-2 and -3 (1971), Mars-5 (1973) and Venera-9 and -10 (1975), which were in many respects the world ‘firsts’.

6

IKI had almost no part in the ASTP program, which ended with legendary docking of Soyuz and Apollo spacecraft on July 15, 1975. But for reasons of secrecy, many Soviet engineers and other people, who really worked in the program, were hired by IKI or introduced themselves as IKI employees, so that they did not name their real affiliations.

IKI hosted the meetings of the working groups on the Soyuz-Apollo program. A control docking of Soviet and American units was also performed at IKI facilities.

During the flight itself, IKI’s staff ran one experiment dedicated to observations of solar corona from one of the spacecraft, while the the second one was eclipsing the Sun.

7

In 1967, IKI’s facilities were reinforced with the State Design and Technology Bureau of Instrument Engineering with an experimental plant in the city of Frunze (now Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan). This new department, or branch, was named the Specified Design Bureau (Russian acronym OKB) of IKI. This bureau did not have its own premises at first. It received the area and the building of a metal bed factory.

The first flight models of scientific instruments developed and built at OKB IKI in 1967–69 were installed on board Prognoz-1, -2 and -3 satellites (from the first to the third). The instruments studied solar activity and its impact on the interplanetary medium and the Earth's magnetosphere. After the collapse of the Soviet Union OKB found itself in the foreign country. In 1993, it changed its name to Aalam Design Bureau (later a joint-stock company), cooperated with the IKI for some time, then it gradually ceased scientific and space work.

8

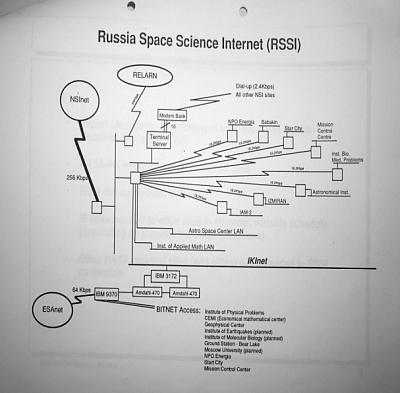

One of the first nodes of Runet — Russian Space Science Internet — emerged in IKI. It happened in 1991−1993 when IKI was connected to the BITNET electronic communication network via a channel operating through Frankfurt, and received international e-mail service. In December 1992, negotiations started on connecting IKI to NASA Science Internet (NSI) network. As a result, in February-May 1994, one of the first Russian Internet nodes was built in the Institute.

9

After the success of VEGA project in 1986, whose aim was to explore Venus and Halley's Comet, IKI was awarded the Order of Lenin. It was presented by the first secretary of the Moscow City Committee of the USSR Communist Party Boris Nikolaevich Yeltsin, the future first president of the Russian Federation. Also in 1986, Pope John Paul II showed interest in this topic. He invited members of the Inter-Agency Consultative Group (IACG) to a special audience. IACG included the heads of space missions, which had performed Halley’s Comet fly-bys. Among them were Academician Roald Sagdeev, head of VEGA project, then director of IKI, and his colleagues from the Institute. The Catholic Church's interest in the project was partly due to the fact that Halley's Comet was depicted as the Star of Bethlehem in one of Giotto's frescoes — for some time there was an assumption that Halley's Comet was the very star that indicated to the Magi the place of Christ's birth. The theory has not been confirmed later, but the connection between the artist's name, Christianity and space exploration led to the appearance of such a photograph.

10

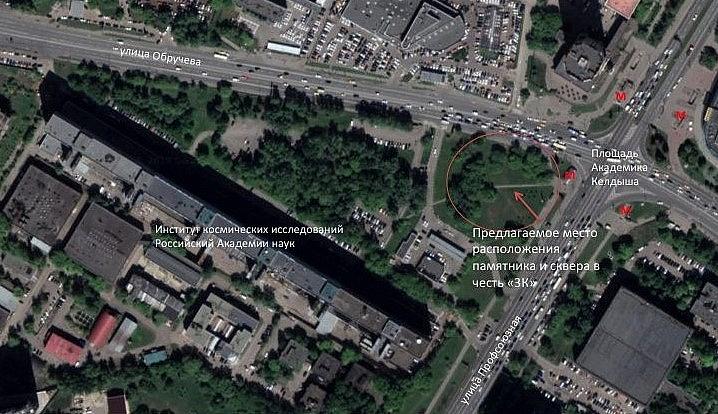

The main building of IKI is located at the intersection of Profsoyuznaya and Obrucheva streets, which is officially Academician Keldysh Square. In 2019, the Russian Academy of Sciences made a proposal to build a monument on the square in honor of M. V. Keldysh and his closest associates — academicians S. P. Korolev and I. V. Kurchatov, the legendary “three ‘Ks’” of the Soviet rocket and space industry.

More about IKI

- IKI History. From the Project of the Joint Institute for Space Research to the 50th Anniversary

- Space Research Institute Russian Academy of Sciences 50 years. М.: IKI RAS, 2015. 296 p.

- Lev Zelenyi. Afterword to foreword: The interview with the director of Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences Academician Lev M. Zelenyi. М.: IKI RAS, 2015. 40 p.

In Russian

- Обратный отсчёт...4. М.: ИКИ РАН, 2016. 216 с.

- 50 лет Институту космических исследований Российской академии наук. Обратный отсчёт... 3. М.: ИКИ РАН, 2015

- К 45-летию Института космических исследований РАН. Обратный отсчёт...2. М.: ИКИ РАН, 2010

- Обратный отсчёт времени. Сборник материалов к 40-летию ИКИ РАН. М.: ИКИ РАН, 2006

And even more

- Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Fund 1962, Space Research Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences

- The Soviet Space Initiative in State Documents. 1946−1964 / Ed. by Y. M. Baturin. Moscow: RTSoft Publishing House, 2008

In Russian

- Советская космическая инициатива в государственных документах. 1946−1964 гг. / Под ред. Ю. М. Батурина. М.: Изд-во «РТСофт», 2008

- Сыромятников В.С. 100 рассказов о стыковке

- Гурштейн, А. А. Московский астроном на заре космического века: автобиогр. заметки. — М.: НЦССХ им. А. Н. Бакулева РАМН, 2012. — 675 с.

- Фрунзенское ОКБ ИКИ: особое конструкторское бюро Института космических исследований Академии наук СССР / [сост. и ред. Вячеслав Викторович Щербаков]. — Калуга: Фридгельм, 2010. — 143 с.

- Келдыш Мстислав Всеволодович. Избранные труды. Ракетная техника и космонавтика / акад. Авдуевский В. С., чл.-корр. АН СССР Энеев Т. М. (отв. ред.). — М.: Наука, 1988. — 496 с.

- Суяркулова М. Передовая периферия: фрунзенское ОКБ ИКИ как «закономерная случайность» позднесоветского развития / П56: Понятия о советском в Центральной Азии: Альманах Штаба № 2: Центральноазиатское художественно-теоретическое издание / Сост. и ред. Г. Мамедов, О. Шаталова. Бишкек: Штаб-Press, 2016. 578 с.

Based on materials from Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the Russian Academy of Sciences, Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences, State Space Corporation ROSCOSMOS, TsNIIMash JSC, NASA, келдыш.рф, pastvu website, and archive of Pravda newspaper.

Special thanks to Oleg L. Vaisberg and Igor A. Lisov for their kind help with the facts and illustrations.

The “first edition” of this page was published in 2020 on the occasion of the 55th anniversary of IKI and used Tilda web designer.